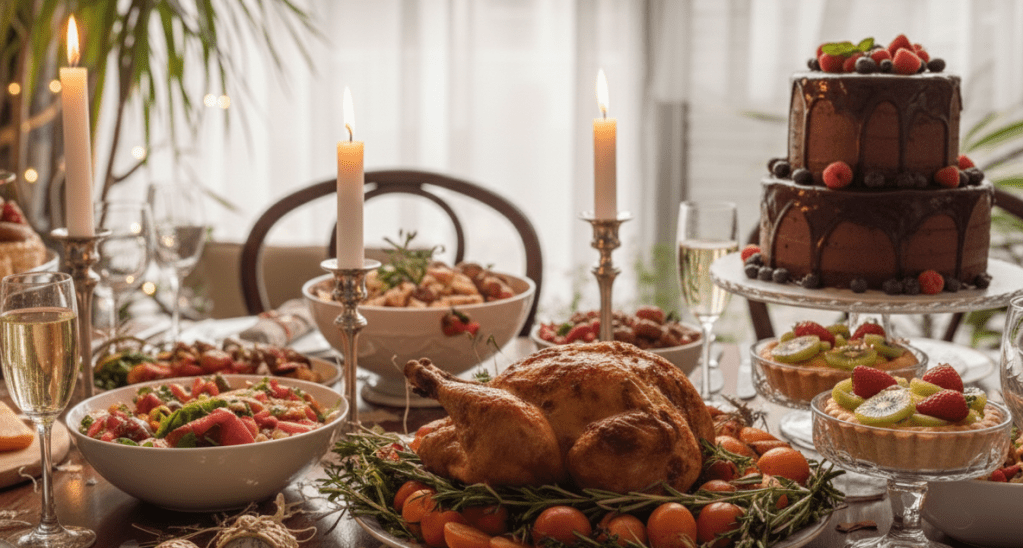

The days between Christmas and the New Year have their own rhythm.

The big moments have passed, but the food remains.

Rich dishes still within reach. Snacks without a particular occasion. Ingredients that quietly shape what gets cooked, simply because they’re there.

From a brain point of view, this is entirely predictable. We’re wired to eat what’s available, especially when it’s energy-dense and feels temporary. When food feels special or fleeting, urgency creeps in, even when there’s plenty.

This is also why this time of year so often gives rise to the idea of a “reset”.

When indulgent food is everywhere, it can start to feel as though it’s about to become permanent, as though a few weeks of abundance might hard-wire themselves into habit. January then gets cast as a corrective: a moment to regain control before things “set”. Hence the well-known January resolution.

But that assumption misunderstands how habits actually form.

Most changes don’t begin with intention

Very few people deliberately decide to change how they eat in a dramatic way.

What usually happens is much quieter.

An ingredient becomes normal in the kitchen.

A different fat goes into the pan because the usual one has run out.

A bake turns out lighter or dairy-free, almost by accident, not because it was planned, but because that’s what the cupboards look like now.

When something is used repeatedly, the brain stops treating it as a compromise. It becomes familiar. And once it’s familiar, it becomes the default.

That’s how most real rewiring happens, not through restriction, but through repetition.

Substitution as exploration, not restraint

Substitutions are often framed as something you have to do.

I prefer to think of them as something you get to try.

They’re a way of learning how ingredients behave, how flavours shift, how your own preferences evolve over time. They invite curiosity rather than compliance.

The most useful substitutions at this time of year aren’t about cutting things out. They’re about gently rebalancing, so leftover indulgence remains satisfying rather than guilt-inducing.

For example:

- Incorporating rich leftovers into everyday meals, so you’re still enjoying seasonal food while naturally drifting back to your normal, nourishing routine. A pea, ham hock and watercress salad is a good example, here, a small amount of ham hock brings depth to a fresh, green dish. Any leftover shredded ham works just as well.

- Transforming Christmas biscuits into a cheesecake base that can be frozen and enjoyed in portions, rather than leaving small temptations scattered around the house. Even better if you invite a friend over and share a slice.

You still get richness where it matters, you just don’t eat it everywhere, all at once.

Over time, this subtly shifts what the body expects from a meal: comfort without excess, satisfaction without overload, nourishment without compromise.

Planning indulgence so it loses urgency

One of the most effective habits I’ve learned when dealing with holiday leftovers is planning. This is where substitutions quietly turn into habits.

Meal prepping, planning, and freezing don’t need to be rigid. Simply deciding:

- what will be eaten today

- what will be portioned and stored

- what will be transformed later

can completely change how leftovers — and January — are experienced.

If leftovers are earmarked for another meal, or dessert is planned for tomorrow, the brain relaxes. There’s no need to eat everything immediately. Scarcity disappears, even though the food is still there.

This matters particularly now, when abundance lingers without structure.

The same principle applies to:

- roasting joints and freezing smaller portions that can later become something special, perhaps the starting point for a first go at a beef Wellington

- choosing simpler preparations that can act as a base for future meals, rather than a one-off dish

- keeping sauces separate, so they can be reused, portioned, or frozen

These small decisions reduce decision fatigue later which is often where good intentions unravel.

Continuity, not correction

When January arrives, the people who feel most settled aren’t the ones who restricted hardest in December. They’re the ones who quietly built continuity.

They know how to live with indulgence, folding it into familiar ways of cooking that feel supportive rather than punitive.

That’s how substitution becomes habit: not through discipline, but through familiarity.

A gentle note

This is also why January resolutions so often feel hard to sustain. They’re framed as a sudden change, when in reality January is simply a return to normal after a period of joy and indulgence.

When that return has been gently anticipated through planning, portioning, and familiar ways of cooking, it doesn’t require willpower. It just happens.

If cooking is starting to feel repetitive or uninspiring, please check the recipe section designed to offer flexible, adaptable ideas — popular dishes that welcome substitutions and work just as well.